This semester the students in Dr. Shah’s Chad 164: contemporary parenting class and Chad 162: Raising children in multicultural societies were tasked with writing an extensive research paper on what the research states when it comes to the best parenting style for children. They had to review cross-cultural research from various countries around the world (e.g., China, Iran, Spain, Brazil, etc.) and compare and contrast child outcomes with one another.

—The What—

We will first address the what.

What are the key characteristics of the parenting styles and what are the outcomes for children? The two dimensions that will be discussed below are how parents provide love & discipline. Nurture has to do with unconditional love, and how responsive a parent is to a child’s developmental needs. Structure has to do with discipline and how parents set boundaries, rules, and consistency in a child’s life.

Authoritarian Parenting

An Authoritarian parent is high in structure and low in nurture. This is the strict parent who demands obedience from the child They have a fixed set of rules and use physical punishment when a child disobeys them. Children are often scared of their parents and therefore, they often don’t talk back. Common phrases are “because I said so” or “it’s my way or the highway!” For example, if it’s time for a child to sleep an authoritarian parent would loudly say “Go to sleep right now!” with a look that makes sure that child knows who holds the power and control in the relationship. It’s a unidirectional style of power, and information always flows from the parent to the child.

The authoritarian parenting style often leads children to lower levels of self-esteem. They also have trouble making decisions because they are often told what to do. The parents often act as bullies in the house telling their children what to do using verbal or physical aggression. Unfortunately, this leads children to either imitate their parents and become bullies with their peers—or it leads children to believe that they are to blame and they become victims of bullying situations. These children do not have their social or emotional needs met and thus, this can show up with externalizing behavior (aggression) or internalizing behavior (anxiety and/or depression).

Authoritative Parenting

An Authoritative parent is high in warmth and high in control. They have clear, consistent rules that they explain to their children. They have logical, natural consequences when a child does not follow the rule. They also provide a rationale for the rules and children know why they exist. Common phrases are “We are doing it this way because…” For example, if a parent was putting a child to sleep, they would not state that “Remember, our family rule is that bedtime is at 8 pm. We want to get enough sleep to make sure our brains and bodies get enough time to rest and develop properly.” It’s a bidirectional style of parenting, so information can flow from the parent OR the child; as a result, parents often compromise and negotiate with their child.

The research on parenting styles has found that even across individualistic and collectivistic cultures, authoritative parenting leads to the best outcomes for children and increased overall life satisfaction (Lavric & Naterer, 2020; Sahithya, 2019; Sorkhabi,2005). Children feel respected and valued in their families. They understand why the rules exist —- and are more likely to follow them when they get older. They develop higher-level critical thinking skills and they have higher levels of self-esteem and confidence. They are also more independent, self-reliant, and have higher levels of self-control.

Permissive Parenting

A Permissive parent is high in nurture, and low in control. They are very responsive to whatever the child needs and they don’t have very many rules for their children. They want to be best friends with their children and they want to be the “cool” parents. Common phrases are “I never say no to my child.” If a parent is putting a child to sleep and the child doesn’t want. to go to sleep they would say, “Sure you don’t have to go to bed if you don’t want to…”

The permissive parenting style often leads children to lack self-regulation skills. They are able to do whatever they want, whenever they want to. As a result, they feel entitled in school and in society. They often have high levels of self-confidence; however, this can lead them to become bullies with their peers because they are raised to believe that they are better than others. They also lack empathy and disregard the needs of others.

Neglectful Parenting

A Neglectful parent is low in control and low in warmth. They are also known as uninvolved because besides providing the basic needs for their children, they don’t provide much more. They don’t prioritize their children because they may be dealing with life stressors: being a young parent, financial stressors, mental health problems, and/or being addicted to alcohol and/or other substances.

The neglectful parenting style is also known as uninvolved or detached parenting. Unfortunately, this leads to the worst outcomes of all 4 parenting styles. Children have low levels of self-esteem and self-confidence. They are more prone to aggression, impulsivity, poor academic performance, and substance abuse. They are more emotionally and socially withdrawn and fear becoming dependent on people.

—The Why—

Why do parents parent the way they do? For some parents, it was the way they were parented (e.g., family-of-origin experiences) and they continue to provide love and discipline in the same way. Because it’s intergenerational, it’s more reflexive, and parents don’t really think about their parenting style, they just go with what naturally comes to them (which is what their own parents did).

For others, it’s just easier not to explain the rules and to command children to obey through fear (authoritarian) —- or to just let them do whatever they want, whenever they want (permissive).

Authoritative parenting is harder because it is time-consuming. Parents have to have a lot of patience to discuss why the rules exist. They also have to follow through with consequences even if it is not convenient for them. In addition, they have to think of logical, natural consequences when a child decides they don’t want to follow the rules that have been set by the families (vs. having the same consequence every time the child misbehaves). A key component of this parenting style is communication and helping children with emotional regulation.

“The prevalence of destructive behaviors in adulthood can be traced back to family-of-origin experiences in which poor and ineffective parenting may have played a major role (Coontz, 2006). Poor preparation for parenthood, inadequate social support, lack of adequate skills for coping with the stresses of parenting and resource-depleted environments all interact to put families at risk (Cheal, 2007).”

In our contemporary parenting class, we talk about how the authoritative parenting style is a protective factor against the negative life stressors children experience. A preventative measure in our society would be to help educate parents on the best parenting style and the best child outcomes. This would decrease externalizing behavior (aggression) and internalizing behavior (anxiety, depression) in children.

If parents knew what the best outcomes were for children they would most likely do their best to reflect on why they may parent in authoritarian, permissive, or neglectful ways—-and we believe, that if they know how (concrete steps + strategies) to implement the authoritative parenting style, they would make an effort to change.

Culture + Parenting Style: How socialization goals can be communicated

In some cultures, other parenting styles have led to beneficial outcomes. For example, Asian American children whose parents practice the authoritarian parenting style, still find that their children have beneficial academic outcomes (Chao 1994; Chao, 2000). However, this isn’t necessarily the case for their child’s social and emotional outcomes. Researcher Desiree Qin notes that many Asian American children deal with an adjustment/achievement paradox: Asian American children have high levels of academic achievement but low levels of psychological and social adjustment. Thus, it is important for parents to meet the emotional needs of their children. It is important to note that the authoritarian parenting style has also been equated with children having poor social skills, anxiety, depression, and poor self-esteem. Research studies have also found that Asian American children are more likely to experience depression and thoughts of suicide due to problems that originate with their families.

In some South American countries, permissive style parenting also has positive outcomes, like higher self-esteem (Martinez et.al, 2020; Garcia, 2020). Some of the research on permissive is mixed because collectivistic cultures often have social norms that have to be followed and this can act as a way of providing structure for them. The age of a child also plays a role as children who are adolescents can benefit from permissive parenting since it allows for more freedom and independence (which is a developmental need for adolescents). However, the research also shows that adolescents’ prefrontal cortex is still developing (which is responsible for thinking through the consequences of their actions) and therefore, they still need their parents to monitor them and check in with them about what they are doing and who they are with.

In the U.S., we have an individualistic culture that prioritizes the individual, their self-esteem, and overall well-being. We want to raise children who are confident, assertive, and who knows what they want in life. Children want to live fulfilling and meaningful lives and as parents, we can help them get there with a parenting style that values who they are, and what they want out of life, and guides them to make the best decisions for their futures.

In collectivistic cultures, parents want to raise children who are obedient and follow the rules. They want their children to respect authority figures, listen to their elders, and follow social norms that are a part of their culture. However, this can also be done with the authoritative parenting style, as it is the most flexible style and allows for parents to communicate their socialization goals (e.g., respect) to their children.

—The How—

How do you practice authoritative parenting? This is going to look different for each age group. This semester, San Jose State students in the Child and Adolescent Development Department did parenting presentations in collaboration with CommUniverCity. The students presented to parents at the Ethnic Wellness Center (EWC).

The student’s presentations were related to how to implement the best parenting style, authoritative, which is a balance of nurture and structure for each of the age groups below. They also created free downloads for parents on best practices.

Here are some of the highlights.

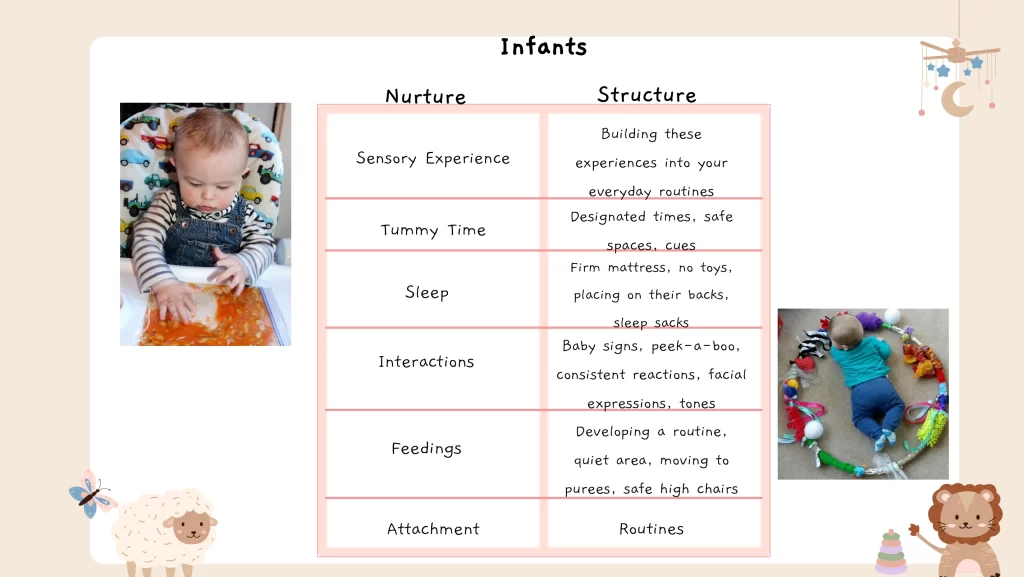

Infants (0-1 year of age)

For example, for infants nurture would be attaching, bonding, and being responsive to an infant’s cues. While structure relates to having routines and creating a safe space for infants (firm bedding, best practices for breastfeeding, quiet room, etc.)

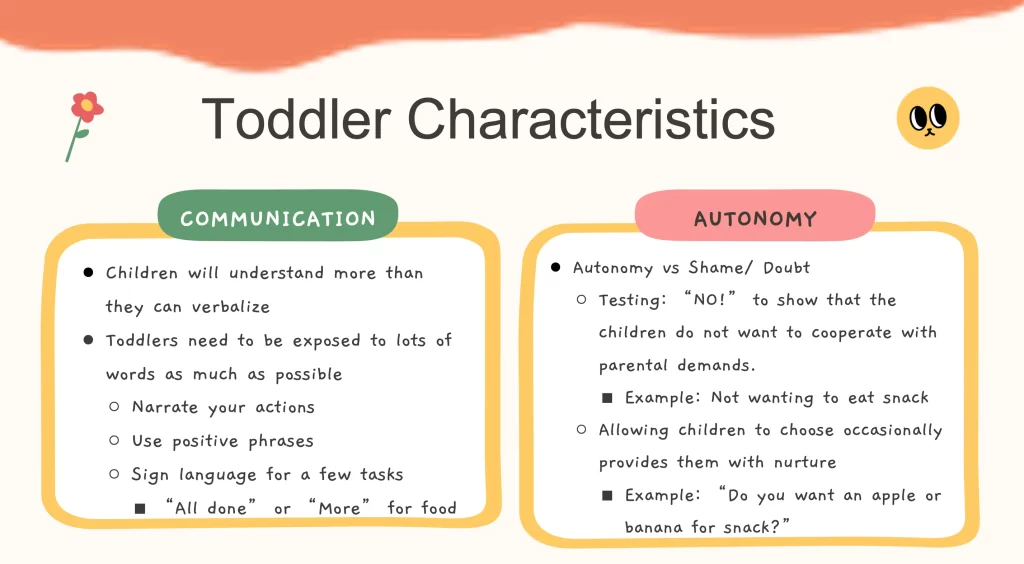

Toddlers (1-3 years of age)

For toddlers nurture is about fostering autonomy and choices in what they wear or do; while structure is about making sure the house is toddler-proofed so toddlers can be successful in exploring their space.

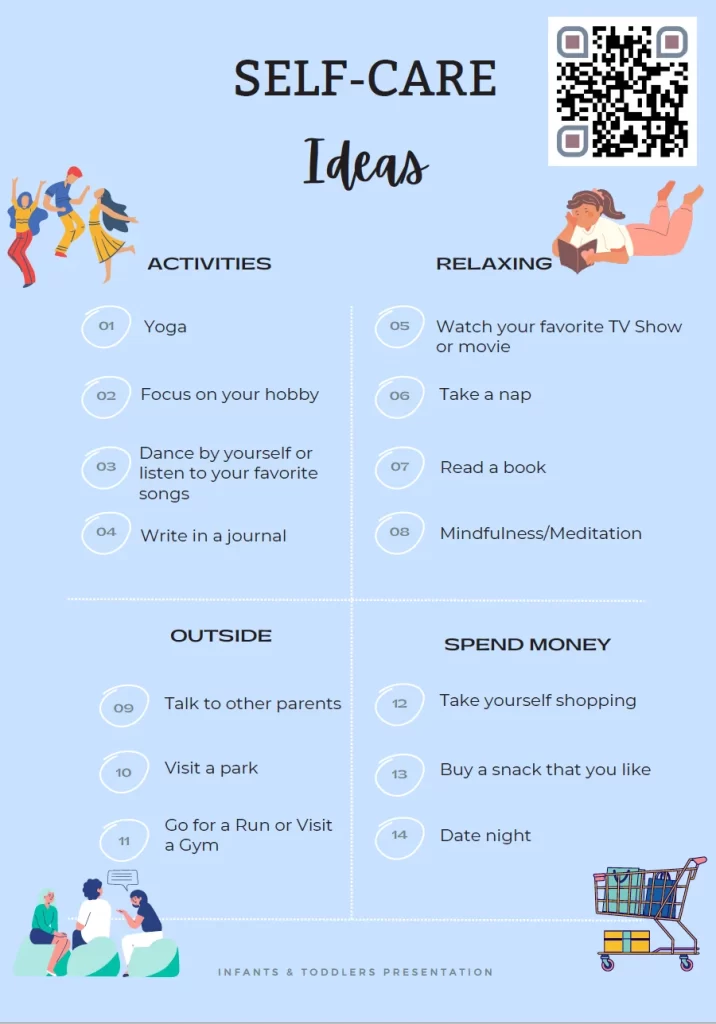

Parents of Infants & Toddlers: parenting at this age can be very physically and emotionally taxing because younger children require constant care. Make sure you spend extra time on self-care so you can provide a balance of nurture and structure.

Click here: Download Self-Care Tips for Parents.

Preschoolers (3-6 years of age)

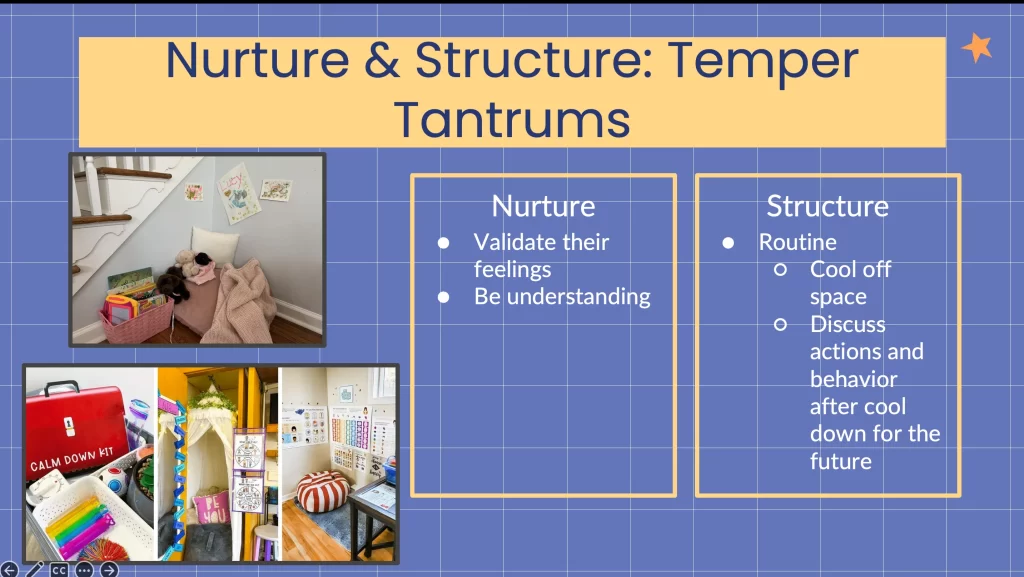

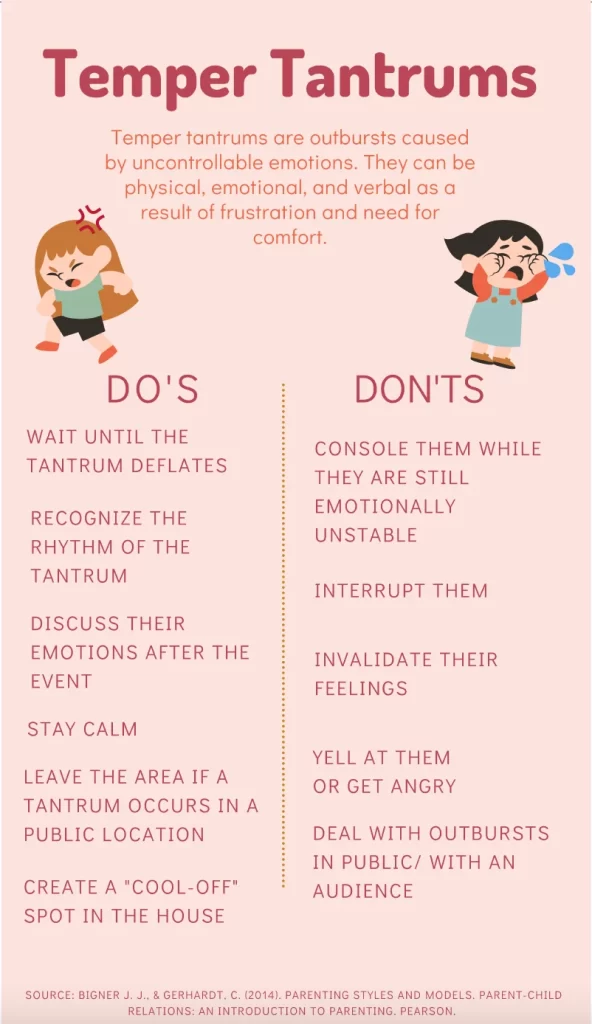

For preschoolers, nurture is about emotional regulation & socialization with peers; while the structure is about having rules and making sure they have a space in the house that allows them to “cool off” from their strong emotions when things don’t go their way. Preschoolers also learn about how some rules are related to safety and are non-negotiable, while other rules can be negotiable.

Parents of Preschoolers: Temprum Tanrums peak at this age; parents can help children regulate their difficult, strong, and uncomfortable emotions when things don’t go their child’s way.

Click here: Download Best Practices for How to Deal with Temper Tantrums.

School-Age Children (6-12 years of age)

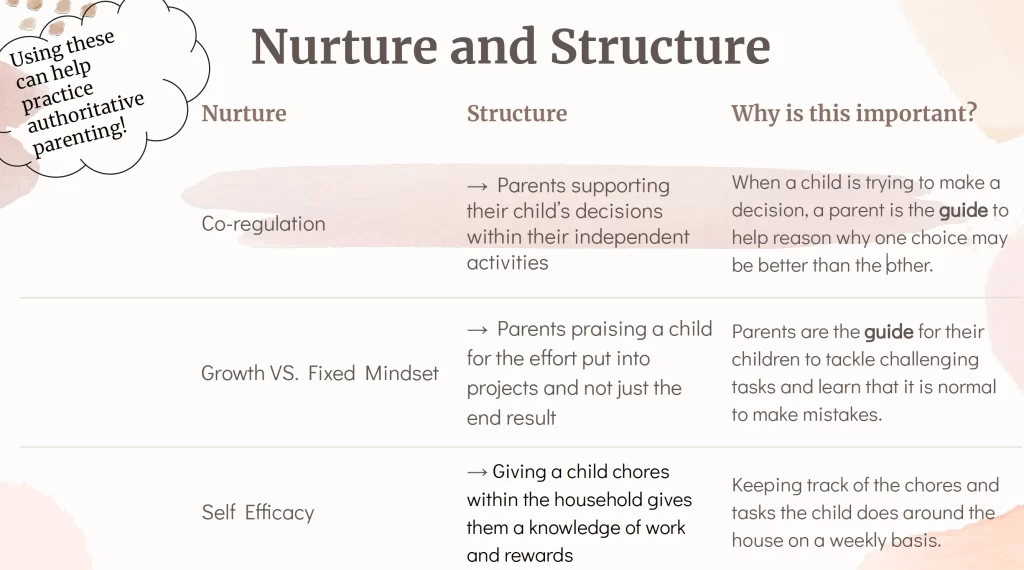

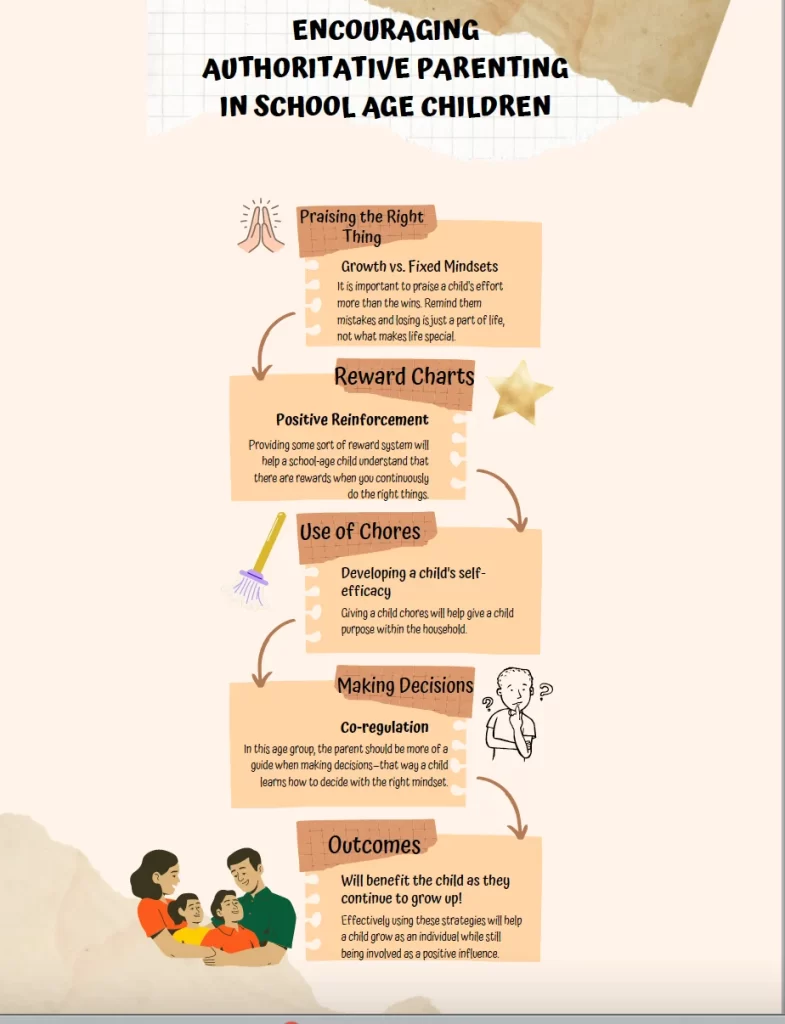

For school-age children nurture is about co-regulation. Parents can help their child co-regulate by being there and being psychologically available when their child gets frustrated with doing tasks independently. Nurture is also about helping them develop a growth mindset. The structure is about making sure they understand why the rules exist and following through with consequences if their children decide not to comply with the rules.

Parents of School-Agers: Parents often have higher expectations of their children and believe they should be able to do activities on their own; however, children at this age still need guidance as they engage in this process of taking care of themselves.

Click here: Download this chart for best practices for School-Age children.

Adolescents (13-18 years of age)

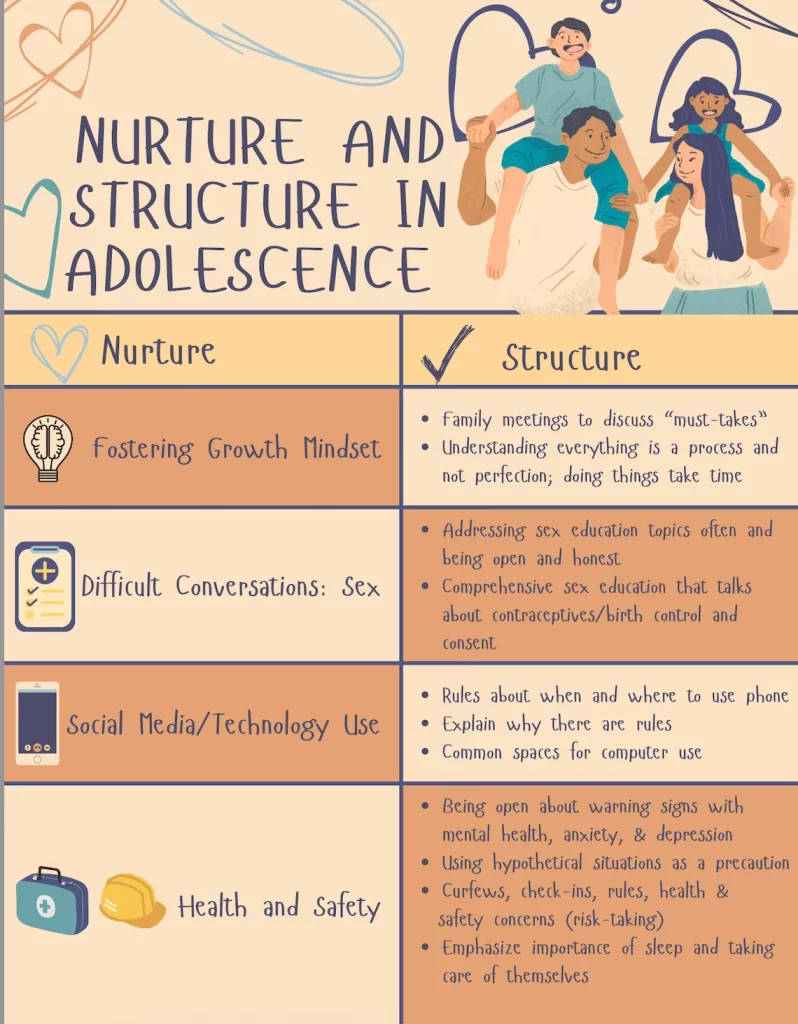

For adolescents, nurture is about fostering independence; while structure is about monitoring them for health and safety risks through check-ins and curfews.

Parents of Adolescents: Balancing nurture and structure is tricky because adolescents need independence from their parents. They also need monitoring because their brains are still developing and they are more likely to engage in risky behavior at this age.

Click here: Download this chart for best practices for raising adolescents.

Family Meetings, Communication & Modeling Emotional Intelligence (EQ)

Another key to authoritative parenting is communicating often with children and checking in to discuss their emotions and feelings. Monthly family meetings are a best practice. Families can meet once a month to discuss what is working, what isn’t working, and family trips—and then they can do a fun bonding activity at the end to strengthen the relationship they have with one another. There is typically an agenda, and everyone gets a chance to speak in a setting that is safe and welcomes input from children and adults on best family practices. Key elements of authoritative parenting as children get older are allowing them to express their opinions and negotiating and compromising. This models healthy ways of resolving disagreements and conflicts within family settings. Through this process, provides children are provided with a model of what healthy relationships look like.

Authoritative parenting does take more time, energy, and patience, but families that practice this way of parenting reap immense benefits. While every parent may prioritize different goals for their children, it is important to remember that we need to put the academic, social, emotional, and cultural needs of our children first. The interactions that we have with our children are shaping the skills they acquire (e.g., reasoning, negotiating, critical thinking) and who they become (e.g., self-confident, responsible, curious, social, and respectful individuals).

References

Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style:

understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child

Development, 65(4), 1111–1119. https://doi-org.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/10.2307/1131308

Chao, R. K. (2000). The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers:

relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of

Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(2), 233-248.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00037-4

Garcia, F., Serra, E., Garcia, O. F., Martinez, I., & Cruise, E. (2019). A Third Emerging Stage for the

Current Digital Society? Optimal Parenting Styles in Spain, the United States, Germany,

and Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13),

2333–. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132333

Lavrič, M., & Naterer, A. (2020). The power of authoritative parenting: A cross-national study

of effects of exposure to different parenting styles on life satisfaction. Children and

Youth Services Review, 116, 105274–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105274

Martinez, I., Garcia, F., Veiga, F., Garcia, O. F., Rodrigues, Y., & Serra, E. (2020). Parenting Styles,

Internalization of Values and Self-Esteem: A Cross-Cultural Study in Spain, Portugal, and

Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 17(7), 2370.

Sahithya, B. R, Manohari, S. M, & Vijaya, R. (2019). Parenting styles and its impact on children –

a cross-cultural review with a focus on India. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 22(4),

357–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2019.1594178

Sorkhabhi, N. (2005). Applicability of Baumrind’s parent typology to collective cultures: Analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. International Journal of Behavioral Development 29(6):552-563.